Otto Hüttner

From Leipzig to the Clyde: Otto Hüttner’s Visit to New Lanark 200 Years Ago Today

Compiled by Tanya Brennan

“A lovely, romantic path through shrubbery and intense green meadows on the banks of the roaring Clyde… This sight was indescribably exalted and awe-inspiring, I shall and will never forget it.”

200 years ago, on 16 August 1825, a young German traveller named Otto Hüttner stood at the Falls of Clyde in Lanarkshire, Scotland, overcome with awe at the beauty before him.

He had journeyed a long way — over 1,000 miles from his home city of Leipzig — to explore Britain, improve his English, and faithfully record his adventures in a diary.

His writings reveal a young man of sharp opinions, boundless curiosity, and infectious joy. Chronicling the people he met, the friendships he forged, and the families who welcomed him along the way, all with high regard and keen observation.

Otto was just 20 years old when he began his journey with his two friends. He turned 21 during his travels, noting in his diary that he wanted to write everything down so that he explains it will,

“Remind me when I’m old and grey

Of youthful ventures long gone by,

And let it show my gratitude

To those who helped me on the way.”

The Diary’s Journey

The two small, leather-bound notebooks containing Otto’s words might easily have been lost to time.

However, they survived thanks to one of his descendants, who undertook the meticulous work of translating Otto’s diary from German into English.Their dedication allows us to hear his thoughts across the centuries, and without it, we might never have known what Otto saw, or how he felt, during his visit.

From Leipzig to New Lanark

In the autumn of 1825, New Lanark was already world-famous as a model industrial village. Founded by David Dale and later managed by his son-in-law, the visionary social reformer Robert Owen, it combined cutting-edge water-powered cotton mills with an unusually progressive social system, offering fair employment, decent living conditions for its workers with their families, and full-time education for their children.

By the time Otto arrived, the mills were owned by Charles and Henry Walker, sons of John Walker, Robert Owen’s wealthy and well-respected Quaker business partner. Like Owen, the Walkers held a humanitarian outlook and upheld high standards for worker welfare.

However, they were neither as outspoken nor as well-connected as Owen or New Lanark’s founder, David Dale, and so this period of the village’s history is less well-documented. (You can learn more about the Walkers and their tenure at New Lanark on our website’s 1825–1881: The Walkers’ page.)

It’s not recorded exactly why Otto decided to come here but given the fame of Owen’s ‘New Moral World’ experiment, it’s likely he was curious to see this celebrated community for himself.

New Lanark as Otto Saw It

On arriving, Otto admired the view from above:

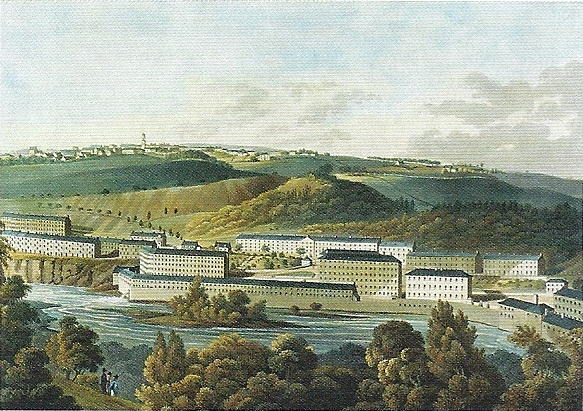

“…we had a very fine view of Mr. Owen & Co’s world-famous factory and school which lie in a valley on the River Clyde and consist of a large number of fine, multi-storey, regular buildings… It is a factory that produces cotton thread and a school for the children of the factory workers… who receive a pretty complete education there free of charge.”

A polite and knowledgeable guide led Otto through the factory:

“There was even a large building in which nothing but the machinery for this factory was made. Everything was water-driven and the water works were interesting. There was also a house where the company sold as cheaply as possible all those items that the workers and their friends were in need of. There were hats, cloth, flour, baked goods, meat, eggs, etc.”

Otto was particularly intrigued by the school, which he wrote was based on the Lancaster system:

“The events of ancient and modern history were drawn in sequence on a long piece of linen and rolled up… The entire course of instruction consists of questions and answers and sensory impressions on the mind. They learn dance and music in this school but no foreign languages.”

“There are a dining hall, a dance floor, a chapel, several school rooms, a number of dormitory rooms, etc. Girls and boys sit together in one room from age 3 to age 12. The building is full of paintings which are used during class.”

However, Otto was not impressed by the children — a view that directly contrasts with Robert Owen’s vision of a clean and orderly classroom filled with respectable pupils. Writing in his diary, he observed:

“The children are not well dressed and some are quite dirty. There is no discipline; the children whistle, yell, and do what they like during class (at least during the period we observed).”

Nature’s Everlasting Impression

For all the industrial wonders he saw, it was the Falls of Clyde that truly stole Otto’s heart:

“Bonnington Falls, which filled me, who had never seen anything like it, with awe and wonderment. I saw a hugely high and wide rock basin into which the river tumbles from cliff to cliff with such force and from such height that much of the water rises from the bottom of the basin as fog and steam. This sight was indescribably exalted and awe-inspiring, I shall and will never forget it.”

Today, visitors can still follow the same riverside path Otto walked, see the waterfalls, and admire the rolling hills and woodlands.

A Glimpse into 1825

Otto’s words offer us more than just a travelogue — they capture a moment in New Lanark’s history when industry, education, and nature coexisted in a unique harmony.

Many of the buildings he saw remain, and visitors can still tour the mills, school, and company store.

As we mark 200 years to the day since Otto’s visit, we’re reminded how travel can connect people across centuries. His curiosity, joy, and appreciation for both human achievement and natural beauty still speak to us today.

A heartfelt thank you to Otto’s relative, whose translation has allowed us to share in his journey, and to Otto himself for taking the time, two hundred years ago, to write it all down.